Nixon and Cookie Monster: The Friendship That Transformed America

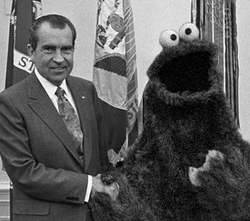

Richard M. Nixon (left) and Cookie Monster, in 1970. Richard M. Nixon (left) and Cookie Monster, in 1970. |

Nixon and Cookie Monster, drawing on recently declassified archives, argues that despite obvious differences in political outlook and ethnicity, these two iconic figures shaped the America we live in today.

Cookie Monster, we learn, began his career known simply as Monster. It was Nixon who advised him that adding Cookie to his name would endear him to the U.S. public. Cookie Monster reciprocated by hatching the “Southern strategy.”

The relationship developed through a mutually advantageous exchange of information and favors. Cookie Monster persuaded Nixon not to cut funding for public television, and in return, used his power behind the scenes at PBS to influence coverage of the president. Nixon was so grateful that Cookie Monster became a frequent presence at Oval Office strategy meetings, where his voice appears on the following tape:

Richard M. Nixon: Who the hell do you think is involved in that last leak?

H.R. Haldeman: Uh —

Cookie Monster: Me know who.

Nixon: Whoever it was, we should set the bureau on that son-of-a-bitch.

Cookie: Me forgot who it is.

John Ehrlichman: Put some —

Haldeman: Yep.

Ehrlichman: Put some heat on him. Because —

Cookie: Wait! Wait! Me remember hear Kermit the Frog say something about it.

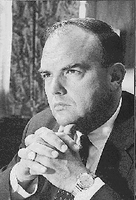

H. R. Haldeman White House Chief of Staff |  John D. Ehrlichman Assistant to the President for Domestic Affairs |  Kermit the Frog Spokesfrog |

This meeting had many ramifications. Kermit was dropped from the Air Force One press pool. All the White House cookie jars were discovered to be empty. And Cookie Monster was sent to China to talk to Zhou Enlai—a secret meeting that paved the way for Nixon’s later visit to Chairman Mao.

Not all of Nixon’s circle trusted Cookie Monster. Henry Kissinger thought he was a maniac. Pat Buchanan called him a hippy. Bob Haldeman died convinced that Cookie Monster was really Deep Throat. Yet the association continued. “By 1972,” Chuck Colson wrote in his memoirs, “Cookie Monster was writing most of Nixon’s speeches. ‘Me not crook’ was one of his. Guys like Will Safire would come in afterwards and jazz up the syntax.”

The intensity of the Nixon–Monster friendship can partly be explained by the traits they shared. As Nixon later told Bob Dole, “Cookie Monster’s a go-getter. He always goes and gets his hands on the dough.”

Cookie Monster has publicly distanced himself from some of Nixon’s decisions, denying in his autobiography, What Else Can Me Say?, that he was told anything about the secret bombing of Cambodia or the assassination of Salvador Allende. But most analysts agree that he was one of Nixon’s closest confidantes. By 1973, Nixon was considering boosting his approval ratings by changing his middle name from Milhous to Marshmallow. Cookie Monster was apparently even considered for the Supreme Court.

It was not to be. After Cookie Monster’s conviction for his role in the Watergate burglary, he spent eighteen months in prison. But he bore Nixon no grudge, becoming a frequent visitor to Nixon’s San Clemente estate, and helping arrange one of Nixon’s earliest attempts at self-rehabilitation, his 1979 appearance as a guest star on The Muppet Show.

The 1980s were a tough decade for both Nixon and Cookie Monster, forced to skulk in the shadows of their more upbeat nemeses, Ronald Reagan and Elmo. Elmo was by 1984 widely recognized as Reagan’s chief policy guru, while Nixon and Cookie Monster made few public appearances, except for occasionally trick or treating together in Orange County.

George W. Bush’s first political appointees, so we are told, included three Muppets—the Swedish Chef, Oscar the Grouch, and Karl Rove.* The author concludes that many of the biggest problems the U.S. faces today—rising obesity, the unrelenting abuse of power by the executive branch, an administrative élite largely manufactured in the Jim Henson Workshop, political discourse conducted at a first-grade reading level, and the prevalence of trans fatty acids—can be traced back to that historic meeting so insightfully portrayed in Nixon and Cookie Monster.

* More recently, all Muppets have been purged from the Bush Administration, according to the recent Congressional testimony of “Scooter” Libby, an orange, bespectacled former Washington gofer.

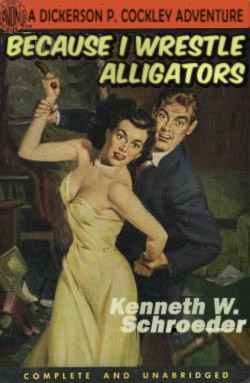

I’m standing in line at the convenience store the other day when I notice someone staring at me. I’m immediately consumed by righteous anger, and grab for the garrote wire and fillet knife I always carry in a sling around my neck. Just as I’m about to put an end to this nosy fucker’s busy, intrusive life, I notice she’s a she, and very hot. I mean hot, like hot enough to make you want to slice off your ear and mail it to her. Well, maybe not that hot. Someone else’s ear then …

I’m standing in line at the convenience store the other day when I notice someone staring at me. I’m immediately consumed by righteous anger, and grab for the garrote wire and fillet knife I always carry in a sling around my neck. Just as I’m about to put an end to this nosy fucker’s busy, intrusive life, I notice she’s a she, and very hot. I mean hot, like hot enough to make you want to slice off your ear and mail it to her. Well, maybe not that hot. Someone else’s ear then …

Oh. My. God. Perhaps the worst-tasting thing I’ve ever put into my mouth, on purpose or otherwise …

Oh. My. God. Perhaps the worst-tasting thing I’ve ever put into my mouth, on purpose or otherwise …